|

Rodney Collin examines 20th-century scientific discoveries and traditional esoteric teachings and concludes that the driving force behind everything is neither procreation nor survival, but expansion of awareness.

Collin sets out to reconcile the considerable contradictions of the rational and imaginative minds and of the ways we see the external world versus our inner selves.

For readers familiar with Gurdjieff’s cosmology will here find further examinations of the systems outlined in by Ouspensky in In search of the Miraculous.

The Theory of Celestial Influence, is an ambitious attempt to unite astronomy, physics, chemistry, human physiology and world history with his own version of planetary influences.

|

The Theory of Celestial Influence

Man, The Universe, and Cosmic Mystery |

| Magistro Meo Qui Sol Fuit Est et Erit Systematis Nostri Dicatum (Master — Sun Which Was Our System is and will be dedicated to) |

|

|

|

Introduction ♦ Table of Contents

Chapter I ♦ The Structure of the Universe … 1

Chapter II ♦ The Times of the Universe … 19

Chapter III ♦ The Solar System … 35

Chapter IV ♦ Sun, Planets and Earth … 49

Chapter V ♦ The Sun … 64

Chapter VI ♦ The Harmony of the Planets … 78

Chapter VII ♦ The Elements of Earth … 92

Chapter VIII ♦ The Moon … 109

Chapter IX ♦ The World of Nature … 123

Chapter X ♦ Man as Microcosm … 138

Chapter XI ♦ Man in Time … 156

Chapter XII ♦ The Six Processes in Man (I) … 172

Chapter XIII ♦ The Six Processes in Man (II) … 189

Chapter XIV ♦ Human Psychology … 204

Chapter XV ♦ The Shape of Civilization … 227

Chapter XVI ♦ The Sequence of Civilizations … 245

Chapter XVII ♦ The Cycles of Growth and War … 269

Chapter XVIII ♦ The Cycles of Crime, Healing and Conquest … 285

Chapter XIX ♦ The Cycle of Sex … 299

Chapter XX ♦ The Cycle of Regeneration … 313

Chapter XXI ♦ Man in Eternity … 334

Appendices … 348

Plates in the text

Line-Drawings in the Text

Tables in the Text

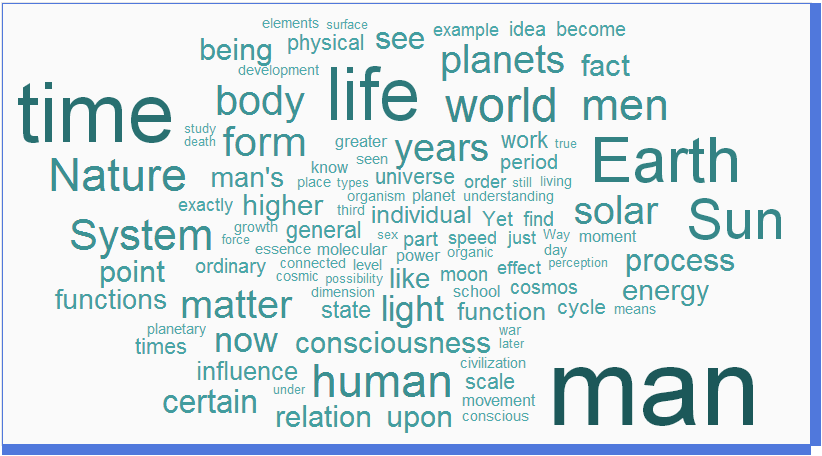

| Characters: Words: Sentences: Paragraphs: Avg. Sentence Length: |

943883 160079 7001 3864 23 |

man 846 (10%) time 532 (6%) life 472 (5%) earth 427 (5%) sun 392 (4%) |

world 304 (3%) men 292 (3%) human 289 (3%) nature 289 (3%) system 270 (3%) |

ARKANA

Published by the Penguin Group Penguin Books Ltd, 27 Wrights Lane, London W8 5TZ, England

Penguin Books USA Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, Ringwood, Victoria, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, 182-190 Wairau Road, Auckland 10, New Zealand

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: Harmondsworth, Middlesex, England

First published in Great Britain by Vincent Stuart Publishers Ltd 1954

Published in the USA by Shambhala Publications 1984

Published by Arkana 1993

35) 79 1058) GF 4e2

Copyright 1954 by Chloe Dickins

All rights reserved

Printed in England by Clays Ltd, St Ives ple

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchase

ABOUT THIS DIGITAL EDITION

This website presents a restored digital edition of The Theory of Celestial Influence.

The restoration corrects transcription errors, missing words, and typographic artifacts found in previous digital versions, while preserving the wording, tone, and meaning of Rodney Collin’s original text. In addition, the eight plates have been digitally restored from source images to improve clarity and legibility while maintaining their original design and informational structure.

Editorial Additions:

Contextual support is provided through non-intrusive glossary tooltips and brief explanatory notes, added only where necessary to clarify terminology that has shifted or become obscure since the time of publication.

Copyright Status:

The copyright of the original text and plates remains with Chloe Dickins and/or their successors and assigns.

No claim is made to the underlying copyright of The Theory of Celestial Influence.

Editorial Contributions:

Text restoration, plate refinements, formatting, and glossary annotations © tonylutz.net, released for scholarly and non-commercial use only. These editorial contributions may be shared under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial–ShareAlike (CC BY-NC-SA) unless otherwise specified.

Use:

You may read, share, and cite this edition for personal or academic purposes.

Commercial redistribution or republication of the restored text, restored plates, or annotations requires permission from the respective rights holders.

|

Rodney Collin Smith was born in Brighton, England, on April 26, 1909. His father was a general merchant who retired from his business in London at the age of fifty, as had always been his intention, and after a journey to the continent and Egypt, settled in Brighton and married Kathleen Logan, the daughter of a hotel proprietor. They lived in a comfortable house on Brighton Front, where Rodney was born. His brother was born four years later.

His mother was interested in astrology and belonged to the local Theosophical Lodge. She spent much of her time transcribing books into Braille for the blind.

Rodney went first to Brighton College Preparatory School (a nearby dayschool), then as a boarder to Ashford Grammar School in Kent. He spent his holidays reading, usually a book a day which he got from the public library, and walking and exploring the neighbouring countryside. On leaving school he spent three years at the London School of Economics, living at the Toc H hostel in Fitzroy Square.

In 1926 he spent the summer holidays with a French family in the Chateaux country, and from then on went every year to the continent. At eighteen he went to Spain, provided by his parents with money calculated to last for a month. By living in inns and farmhouses and in the cheapest hotels and walking much of the way he managed to tour Andalusia for three months, returning with voluminous notes which formed the material for Palms and Patios, a book of essays published by Heath Cranton in 1951. During this trip he learned enough Spanish to cause his being drafted into the censorship during the war and greatly to facilitate his orientation in Mexico in 1948.

On leaving the London School of Economics where he had taken his B.Com., he earned his living by free-lance journalism on art and travel, contributing also a series of weekly articles to the Evening Standard and Sunday Referee on weekend walks round London. For a time he was secretary of the Youth Hostels Association, editor of their journal The Rucksack and assistant editor of the Toc H Journal.

In 1929 he visited Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. On a pilgrimage organised by Toc H to the Passion Play in Oberammergau in 1930 he met Janet Buckley, his future wife. In the same year he read A New Model of the Universe by P. D. Ouspensky. He felt that he was not ready for it yet, but that it would be very important for him later.

In the autumn of 1931 he went on a walking-tour through Dalmatia, later describing some of his adventures there in two articles that appeared in the Cornhill Magazine.

He and his wife were married in London in March 1934, and spent their honeymoon walking in Cornwall. Later in the year they spent six weeks in Sicily. In 1935 they were introduced to some lectures given by Dr Maurice Nicoll, but shortly after left for a six-months’ motor journey through the United States to the west coast, returning along the Mexican border.

In the autumn of 1936 he and his wife first met Mr Ouspensky. Rodney immediately recognised that he had found what he had been searching for in his reading and travels. From then on he dedicated all his time to the study of Mr Ouspensky’s teaching.

His daughter Chloe was born in 1937. He and his family moved to a house in Virginia Water near Lyne Place, which Mr and Madame Ouspensky had taken as a centre for their work. When not at Lyne Rodney spent much of his time in the British Museum Library studying those aspects of religion, philosophy, science and art which seemed most immediately connected with Mr Ouspensky’s lectures. That year he and his wife went on a short holiday to Roumania and later for a two-weeks motor trip through Algeria to the north of the Sahara.

In 1938 he took part in a demonstration in London of the movements and dances which formed part of the system taught by Mr Ouspensky, and immediately afterwards went to Syria in the hopes of seeing the ‘turning’ of the Mevlevi Dervishes. This he was unable to do, though he met the sheikh of the tekye in Damascus.

On the outbreak of war he and his family moved to Lyne Place. Shortly after, his wife and daughter went to the United States to help prepare a house in New Jersey for Mr and Madame Ouspensky, who planned to move there within a few months. Rodney remained at Lyne, working in London in the censorship during the day and in the local air raid defence at night. In February 1941 he was transferred to Bermuda, by coincidence on the same ship on which Mr Ouspensky travelled to the United States, to which Madame Ouspensky had gone a few weeks previously.

After six months in Bermuda Rodney joined the British Security organisation in New York. For the next six years he and his family lived at Franklin Farms, Mendham, a large house with gardens and farm where work was organised for the English families who had joined Mr and Madame Ouspensky and numerous others who attended Mr Ouspensky’s lectures in New York. Rodney commuted to and from his office by train every day and spent the evenings and weekends on the farm.

In 1943, he was sent to Canada on official business. In 1945, 1944 and 1945 he spent his short leaves from duty in Mexico, to which country he was strongly attracted. When war ended he left British Government service and devoted himself entirely to the work of Mr and Madame Ouspensky.

Gradually, however, he spent more and more time with Mr Ouspensky, driving him to and from New York for his meetings and usually spending the evening with him at a restaurant or in his study at Franklin Farms. He became deeply attached to Mr Ouspensky in a way that included, without being limited by, personal affection and respect. While formerly he had concentrated on Mr Ouspensky’s teaching, it was now the teacher and what he was demonstrating which occupied Rodney’s attention.

Mr Ouspensky returned to England in the early spring of 1947. Rodney left Mendham just before Easter, spending a week in Paris before joining Mr Ouspensky at Lyne Place. He was with him constantly all summer and autumn until Mr Ouspensky’s death on October 2, 1947.

The experiences that Rodney went through at this time profoundly affected his whole being. During the week following Mr Ouspensky’s death he reached a perception of what his future work was to be. He realised that, while attached to his teacher for and through all time, he must reconstruct in himself what Mr Ouspensky had given him and thereafter take the responsibility of expressing it according to his own understanding.

He moved to London, where he and his wife lived quietly for the next six months. During the previous summer he had begun The Theory of Celestial Influence, and finished it in the spring of 1948. Many people came to see him at his flat in St. James’s Street, where weekly meetings were held, attended by a number of the people who had worked with Mr Ouspensky, some of whom were to join him later in Mexico.

In June 1948 he and a small party left for New York en route for Mexico, which he felt was his place for a new beginning.

They spent six months in Guadalajara. Here Rodney finished The Theory of Eternal Life, which he had begun in London, and wrote Hellas, a play. Then they moved to Mexico City and after a few months took a large house in Tlalpam, where they were joined by a number of friends, many from England. Meetings were started in a flat taken for the purpose in Mexico City and attended by a number of Mexicans and people of other nationalities. For a time there were meetings in both English and Spanish, until those of the English-speaking group who remained had learned sufficient Spanish to participate in joint meetings conducted in the latter language. The nucleus of a permanent group was gradually formed.

In the spring of 1949 the first translations into Spanish of Mr Ouspensky’s books were begun. These were subsequently published by Ediciones Sol, which Rodney formed for the purpose. During the following years some fourteen titles were published, which included books by Dr Nicoll, Rodney himself, and several others connected with the Work. A number of booklets were also published on different religious traditions which Rodney felt to be expressions of related ideas.

One of the chief plans which Rodney had visualised during the week after Mr Ouspensky’s death was for a three-dimensional diagram expressing simultaneously the many cosmic laws which were the basis of their studies — a building through which people could move and feel its meaning. In 1949 a site in the mountains behind Mexico City was acquired and in 1951 the foundation stone of what is now known as the Planetarium of Tetecala was laid. Tetecala means ‘Stone House of God’ in Aztec, and happened to be the name of the field in which it is situated. This building became the focal point of Rodney’s work with his people during the subsequent years.

In the spring of 1954 it was decided to leave the house at Tlalpam. Twelve public performances of Ibsen’s Peer Gynt were given in the garden as a demonstration of group work, under the name of the Unicorn Players. Rodney played the part of the Button Moulder. Later that year, those who had lived at Tlalpam moved to individual homes in Mexico City.

In 1954 and 1955 Rodney made journeys to Europe and the Near East, the basic reason for which was to collect material of and make connections with esoteric schools of the past. On his visit to Rome in 1954 he was received into the Roman Catholic Church, a step which he had been contemplating for some time.

As a consequence of the distribution of the Ediciones Sol books in Latin America groups were started in Peru, Chile, the Argentine and Uruguay, and contacts made in several other countries on the American continent. In January 1955 Rodney visited the groups in Lima and Buenos Aires and went to Cuzco and Maccu Picchu to study the remains of their ancient civilisations.

In the autumn of 1955 the Unicorn Players produced The Lark, a play by Jean Anouilh about Joan of Arc, in which Rodney played Bishop Cauchon.

In January 1956 he led an all-night pilgrimage on foot from the Planetarium to the shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, some 50 miles. During Mass in the Basilica he apparently fainted from exhaustion, though later it seemed evident that this was the first of a series of heart attacks from which he died in Peru on May 5, 1956.

— Janet Collin Smith

|

Cuzco

Probably the manner of each person’s death is consistent with the manner of his life. Rodney had never spared himself physically, and in the last weeks, although suffering from an exhaustion that was obviously extreme, drove himself to hold daily meetings in Lima, innumerable private conversations and long hours of Movements. He admitted to feeling ‘rather strange’ in the high altitude of Cuzco — 11, 800 feet — and contrary to his life-long habit of avoiding medicines took several doses of coramine.

The day he arrived he found a cripple beggar-boy in the cathedral. After lunch, while the others in the party were resting, he took the boy up the mountain to the great statue of Christ that overlooks the town to pray that he might be healed. Then they went to the public baths where Rodney washed him with his bare hands and dried him with his own shirt. He then bought him new clothes. Outside the shop a crowd had gathered, intrigued that a foreigner should concern himself with a poor Indian boy. Rodney said to the crowd: ‘This boy is your responsibility. He is yourselves. If you pray to Our Lord to make him well, he will be healed. You must learn what is harmony; you must learn to look after each other; you must learn to give — to give.’ Someone in the crowd said: ‘That’s all very well for you — you’re rich.’ Rodney answered: ‘Everyone can give something. Everyone can give a prayer. Even if you can’t give anything else, you can always give a smile; that doesn’t cost anything’

That night a few people came to Rodney’s room in the hotel to ask him about his work. During the conversation a man said: ‘All my life I have wanted to pray, but have never been able to.’ Rodney said: ‘And what do you think you are doing now? What you just said, isn’t that praying?’

Next day the boy came to take Rodney to the belfry of the cathedral to show him where he was allowed to sleep in a comer under the bells. To reach it there is a. climb of ninety-eight steps. Afterwards Rodney went with the rest of the party to visit Inca ruins in the mountains.

After lunch, again while the others were resting, Rodney went out. He climbed up to the cathedral belfry to find the boy and sat on the step below the low containing wall, below an arch. He told the boy that he was going to arrange with a doctor to operate on his twisted leg. While talking he was looking at the statue of Christ on the mountain opposite. Suddenly he got up with a gasp as though his breath had failed, staggered forward onto the top of the low wall, grasping the two wooden beams that were supporting the arch. Then he fell forward, striking his head against one of them. His body fell onto the wide cornice that juts out below and slipped off, falling to the street below. He lay where he fell, his arms out sideways in the form of a cross, his eyes open as though looking up at the sky, smiling.

It is not unusual for a man to die of a heart attack after climbing a long flight of steep stairs at such an altitude after weeks of physical effort in a state of exhaustion. It is the natural consequence of physical conditions. It is also natural, on a different level, for a man who has believed with all his being that the object of life is to give all he has for the love of God, in the end to give himself.

On his tomb in the cemetery in Cuzco are engraved the words he wrote two months before his death:

I was in the presence of God;

I was sent to earth;

My wings were taken;

My body entered matter;

My soul was caught by matter;

The earth sucked me down;

I came to rest.

I am inert;

Longing arises;

I gather my strength;

Will is born;

I receive and meditate;

I adore the Trinity;

I am in the presence of God.

From: Bardic Press

Rodney Collin, born Rodney Collin Smith, was one of the students closest to P.D. Ouspensky. He was born in 1909 in Brighton on the south coast of England. He attended the London School of Economics and became a professional writer and an enthusiastic hiker. His first book, Palms and Patios, was an account of a walking tour through Spain, and was published in 1931, when he was twenty-two years old. During the early 1930s he wrote for a variety of English publications such as the Evening Standard, the Spectator and the New Statesman, and was on the team for the Daily Express Encylopaedia. He joined a number of organizations that were typical of the interests of the time — Toc H (a Christian society), the newly formed Youth Hostel Association, and finally the Peace Pledge Union, an extraordinarily popular pacifist movement that appeared in the run up to World War II. He was evidently searching for some meaning in life, and contributed actively to each of these societies, moving from one to the other, editing both the Toc H journal and the YHA newsletter the Rucksack. He met his wife, Janet, on a Toc H pilgrimage to the passion play at Oberammergau in 1930.

In 1931 he read a New Model of the Universe by P.D. Ouspensky, and in 1935 he and his wife attended some talks given by Maurice Nicoll, who had been a pupil of both Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, but he did not continue with Nicoll’s meetings. Through one of the members of the Peace Pledge Union, Robert de Ropp, he was introduced to Ouspensky’s lectures.

Rodney and Janet became active members of Ouspensky’s group, which was going through a period of expansion and increased activity. He attended lectures and meetings, and worked in the grounds of Lyne Place, a large house in Surrey devoted to Ouspensky’s activities. 1938 saw a presentation of Gurdjieff’s movements, and a visit by Rodney to Damascus and Aleppo, where he contacted the Mevlevi dervish groups. The Collin Smiths bought a house in Virginia Waters to be closer to Lyne, and their daughter Chloe was born. Rodney worked in the gardens and spent many hours in the British Library, studying esotericism, art and civilizations.

The Second World War led to a reduction in the activities of Ouspensky’s groups, and the situation in London eventually became so difficult, with blackouts and the loss of Ouspensky’s private flat and Colet House, that Ouspensky had to move to America in order to keep his groups going. Janet and Rodney assisted in the buying of Franklin Farms in Mendham. Rodney worked as a censor in the British Security Commission, which enabled him to transfer to New York, by way of Bermuda. He travelled to America, by chance, on the same ship as Ouspensky did, the S.S. Georgic, and hence had some closer contact with his teacher.

America brought difficult times for Ouspensky. A number of the more influential English students were able to establish themselves in New York, but much had to be built again from the beginning. Ouspensky was drinking heavily and many of his older pupils have written critical accounts of this time. But after a dramatic evening when Collin confronted Ouspensky, Collin realised that Ouspensky was actually living the work and that much more could be learned from him. After this, Rodney Collin began to take a more active role in Ouspensky’s work, spending a lot of time with Ouspensky and eventually leading meetings for him.

By 1947 Ouspensky was suffering from advanced kidney disease. In January he returned to England and Lyne Place. Rodney followed in the Spring, and the last months of Ouspensky’s life were a time of miraculous possibility and intense change for Rodney. Ouspensky led a series of meetings which threw his pupils back on their own resources. He said that he abandoned the system. For many this was the end of the road, but Rodney found that many things began to come together for him from now onwards. Collin’s intimate and inspiring account of this period, entitled ‘Last Remembrances of a Magician’, was circulated soon after Ouspensky’s death, but has never been published. In August Collin wrote the outline to The Theory of Celestial Influence, a study of man and the universe according to the cosmological ideas of laws of the system.

In September, Ouspensky planned to sail back to America, but at the last moment refused to do so. His final few weeks were filled with extraordinary efforts. When Ouspensky died on October 2, Rodney locked himself away in Ouspensky’s rooms for a number of days without food. When he emerged he seemed by many to have changed. In the following months he wrote ‘Last Remembrances’ and The Theory of Eternal Life.

In 1948, along with a few followers, Rodney and Janet moved to Mexico, which he had visited a number of times during the war. They lived in Tlalpam for a couple of years. The Theory of Eternal Life was published anonymously in 1949, and around this time he wrote ‘Hellas’, a play concerned with the different stages of Greek civilization. He continued to work on the Theory of Celestial Influence, which was finally published in Spanish in 1953 and in English in 1954.

During this time Collin’s group held regular meetings, and he purchased land outside of Mexico city for group work. During the week after Ouspensky’s death he had conceived the idea of a building based on the enneagram and the diagram of the four circles used in Eternal Life. Work began on the building, which took many years and was never finished.

By 1953 Collin was entering into a new period of work. The idea of harmony became central to his aim, and he attempted to establish connections to the other groups who tried to continue the work of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky. He had good relations with Maurice Nicoll, whose books Rodney had had translated into Spanish and were published in Mexico by Ediciones Sol, but Dr Nicoll died that year. He visited Mendham again, but found both the other students of Gurdjieff and Ouspensky strangely lacking in any ongoing sense of the miraculous.

A number of new Mexican pupils joined, among them a lady named Mema Dickens, who began channeling messages from Ouspensky. Collin took these seriously, and this opened up an unbridgeable gap between him and the majority of the other work groups. Collin wrote and published a number of small pamphlets, among them ‘The Herald of Harmony’, ‘The Christian Mystery’ and ‘The Pyramid of Fire’. He converted to Roman Catholicism in 1955 and traveled in South America, Europe and Asia, looking for the traces of the Fourth Way, allowing himself to be guided by the messages he was receiving from Ouspensky. During this time he drove himself very hard physically, taking little rest. In early 1956 he collapsed, and seemed in retrospect to have suffered a heart attack after a marathon pilgrimage to a cathedral. In May he, his wife, John Grepe and Mema Dickens left to visit Rodney’s group in Peru. While the other party members were having a siesta he climbed to the top of a cathedral tower along with a beggar boy whom he was helping, suffered another heart attack, and fell out of the tower into the cathedral square, where he died.

Rodney Collin’s writings include:

Palms and Patios

Written when he was twenty-one years old, this is a vivid account of his travels in Spain.

The Whirling Ecstacy

A translation of part of Les Saints des Derviches Tourneurs, itself a translation of Aflaki’s Lives of the Gnostics. This looks at Rumi and his friend and teacher Shems-ed-din.

Last Remembrances (of a Magician)

Distributed in typescript, but never published, this is Collin’s intimate and unpolished account of Ouspensky’s last months.

The Theory of Eternal Life

Written after Ouspensky’s death, this intense book unites the various theories about death, the soul, recurrence, reincarnation and immortality.

Hellas

A verse drama which looks at different stages of Greek civilization, with Homer, a Socrates and Plato who resemble Gurdjieff and Ouspensky, and Plotinus and Porphyry.

The Theory of Celestial Influence

Collin’s monumental work. Begun as a classification of the sciences according to the ideas of the System, it grew to include the universe, man, and civilization, all looked at from the point of view of ideas such as the Law of Three and the Law of Seven and the enneagram.

The Pyramid of Fire

One of a series of pamphlets. This one investigates the ancient gods of Mexico.

The Mysteries of the Seed

Based around the Greek Mysteries, the authorship of this pamphlet is disputed, and it is my current opinion that, while it was definitely published by Collin, he was not the author.

The Herald of Harmony

A poetic look at school and civilization from the beginning of time until the new civilization of which Collin felt he was a forerunner. Collin sees Gurdjieff and Ouspensky as two poles of a work designed by Higher Forces.

The Christian Mystery

The events of the drama of Christ and the unfolding of Christian civilization are placed on the enneagram.

A Programme of Study

Issued for his groups, this pamphlet outlines many of the general ideas that they studied.

Lessons in Religion for a Skeptical World

A posthumously issued pamphlet, consisting of notes and fragments, mostly with a religious perspective, some of which have probably been revised by his students. A second part to this was published in Spanish only.

The Theory of Conscious Harmony

A posthumous collection of excerpts from letters. Collin was a great letter writer, and these excerpts, organised by topic, offer an encouraging and emotional perspective of the Work. Unlike some of the other posthumous publications, Conscious Harmony is entirely authentic.

The Mirror of Light

Collected from his notebooks, this feels more authentic than Lessons in Religion, but still contains some writings that were probably not Collin’s. A second collection was issued in Spanish only, entitled La Nueva Luz.

Biographical:

Beloved Icarus

Beloved Icarus is an astrological approach to Rodney Collin’s life, written by his sister-in-law, Joyce Collin-Smith

Call No Man Master

by Joyce Collin-Smith. Her memoirs provide the fullest first-person account of Rodney Collin.

Call Man No Master is back in print, buy through Amazon.com

Interview with Joyce Collin-Smith

The first half of an interview by William Patterson that covers the same ground as Joyce Collin-Smith’s published works.

Gauquelin’s Legacy: New Evidence for Planetary Types

An earlier article by Anthony Cartledge, author of Planetary Types.

Gary Lachman, author of the new Ouspensky biography, In Search of P.D. Ouspensky wrote an article on James Webb for the Fortean Times, which mentions Collin.

The Damned

Gurdjieff International Review

Rodney Collin

A Man Who Wished To Do Something With His Life

Terje Tonne

Since I first came into contact with Rodney Collin’s writing, his simple and honest approach to life and the Gurdjieff Work has always struck me deeply. Whether it is in his books, collected notes, unpublished manuscripts or his personal letters—it’s always there.

Rodney Collin-Smith was born on the 26th of April 1909 in the coastal town of Brighton, England. His father, Frederick Collin-Smith, had retired early from his business as a general merchant in London and after traveling in Europe and Egypt had settled down in Brighton. There Rodney’s father married Kathleen Logan, much younger than he and the daughter of a local hotel owner. Kathleen was a member of the local Theosophical Society and had a strong interest in astrology, possibly the source of some of Rodney Collin’s later interests. She also worked extensively with transcribing books for the blind.

|

After boarding school at Ashford Grammar School in Kent, Rodney Collin studied at the London School of Economics, where he received his Bachelor of Commerce degree. He worked as a freelance journalist supplying articles on art and travel to the [London] Evening Standard and the Sunday Referee. In 1930, on a pilgrimage organized by the Christian organization Toc-H, he met Janet Buckley. That same year he read Ouspensky’s A New Model of the Universe. Four years later, Collin and Buckley married in London.

In 1935 Collin and Buckley attended some lectures given in London by Maurice Nicoll. After meeting Ouspensky in September 1936, Rodney Collin knew instantly that he had found that which he had been looking for in his extensive reading and traveling. Robert de Roop, at that time also a member of Toc-H, was most likely a source for their developing interest in the Work ideas. Regardless of what perspective one assumes for a description or interpretation of Collin’s work, it is not possible to overstate both the direct and the indirect influence of Ouspensky. Their approaches seem inseparable.

Ouspensky’s role, actions, understanding and level of being have often been the subject of debate. Historical data can be contradictory and the facts are often disputable. A bystander’s experience may collide with rumors, speculations, half-truths, slander and historical investigation. An unpublished manuscript by Rodney Collin, given to me by the daughter of one of Ouspensky’s older students, indicates that some published interpretations may be incorrect. After their 1936 meeting, Rodney Collin became regularly engaged in Ouspensky’s activities, with the exception of certain periods during the war when Collin was working for the British Government service. After 1945 he dedicated himself entirely to the work with Mr. and Madame Ouspensky.

When Ouspensky left America for England in early 1947, Rodney Collin joined him at Lyne place. When Ouspensky arrived, he asked right away that arrangements be made for his return to America. Detailed preparations for his departure began in the middle of July. Then, in the early morning of September 4, 1947, a truck with baggage travelled down to a ship at Southampton and was brought on board. At about four o’clock Ouspensky called the people that were to travel with him, each in turn, and said: “I cannot go in these conditions.” To Rodney Collin, Ouspensky added: “I thought to take a holiday, but I decided not.” All activity at Lyne and Mendham came to a halt. This incident has historically been interpreted as if Ouspensky changed his mind because of his medical condition. Rodney Collin saw it differently.

Not only did Collin recognize Ouspensky’s decision as a general stop to the impetus of arrangements in both England and America, but also as a test that Ouspensky created for every individual concerned: “As a result of this general test and the sudden interruption of all activity, the stage was automatically set and the characters arranged for what he later proposed to do.” That this event was part of a larger play became more obvious when their automobile was leaving the docks of Southampton with Rodney Collin sitting in the front. Ouspensky leaned forward and said very directly to the four people in the car: “You know I never intended to go to America—not for a minute.”

During the whole summer and autumn, Rodney Collin stayed with Ouspensky until Ouspensky died on October 2, 1947. This period was a critical one to Collin who was an eyewitness to the changes that took place in Ouspensky up to the moment of his death. No historical investigations can negate the account of Collin’s eyewitness experience. Their relationship grew extensively as Collin’s attention moved from Ouspensky’s oral teaching to his demonstrations of the Work.

It was during the week following his teacher’s death, while he locked himself up in Ouspensky’s dressing room refusing to come out, that Rodney Collin felt he really came to an understanding of how to Work. What he had received from Ouspensky had to be reconstructed within himself. Joyce Collin-Smith, Rodney’s sister-in-law (with whom I was very close the last 13 years of her life) told me that during this time, Rodney received in a vision many interpenetrating levels of existence which he later presented in his book, The Theory of Eternal Life. He also told her, years later in Mexico, that during his period of solitude in Ouspensky’s chamber, he had a constant inner experience of extraordinary power and depth and that he knew that he must not be disturbed until it was over.

In her book, Call No Man Master (Bath England: Gateway, 1988), Joyce refers to some papers that Rodney showed her in Mexico in the 1950s. These papers contained certain details of his relationship with Ouspensky that are not public knowledge and that she presumed were destroyed. Some years ago these papers were, for some reason, given to me. I sent a copy to her which she read with interest. Although it appeared clearly in some of the compiled notes in The Theory of Conscious Harmony how important the circumstances around Ouspensky’s death were for Rodney, the unpublished manuscript gives a more immediate sense of intensity and depth of the event.

~ • ~

When in May 1947 Ouspensky “abandoned the system” and urged people to “reconstruct it all,” Rodney Collin, who was then his most intimate pupil, concluded that this was a necessary shock “forcing people to penetrate to what they really understood and wanted in their hearts.” Others saw this “abandonment of the system” as an expression of Ouspensky’s stagnation, while some took it to be a signal for the necessity to look elsewhere for what they believed was missing.

Rodney Collin took the reconstruction to mean: “abandoning old forms, penetrating to the truth which lay behind those forms, and creating new forms for that truth—which in their turn must one day be abandoned also. Abandoning and recreating seems to me the only way of keeping alive the hidden connection which lay behind the system. If one clings to the old, it fossilizes, with oneself inside. The idea of reconstruction seems to be endless.” Here Collin not only illustrates how truth survives through change and renewal and portrays fundamental pitfalls, but he also indirectly points to the essence of form; its nature is to carry content.

Rodney Collin felt little surprised when Ouspensky rejected the old language, the method and the System, that he hardly looked for an explanation. To him, the “System” had become so overwhelming and so complete, that in many cases, including his own, it had begun to strangle his deep inner curiosity and his struggle with the unknown. To Rodney Collin “the abandoning” was an incomplete phrase. He himself heard Ouspensky later say “Yes, I said abandon, not destroy.” It has become clear from this unpublished material that many of the incidents that have been taken as indications, and even proofs of Ouspensky’s unstableness and degeneration, were in fact forms of preparation for himself and his closest circle.

It is difficult to say when these preparations started, most probably before he left America, but definitely by the beginning of April 1947, when Ouspensky started to spend more time in his rooms at Lyne, only seeing a small group of people. From Rodney Collin’s unpublished material, we can see how this group formed and grew both in awareness and understanding: “Yet there was something rather strange about this isolation. Before leaving America, he had written to Lyne saying that he was coming to see certain people ‘whom he would choose.’ On the very day of his arrival he did in fact invite one or two people to come and sit with him or to dine. But curiously enough, after the first invitation, nearly all these people found themselves too busy to respond. Some had unavoidable duties on the farm or business in London, which they regarded as Work—and so were never available when called for. Others came once, but finding that nothing was said or done, felt it rather a waste of time. Unaccepted invitations were not repeated.”

It was through Ouspensky’s ever increasingly economy with words, and his turning of the small group’s attention to seemingly insignificant things—the turning of day and night upside down and the long hours of silence—that Rodney Collin describes what can be recognized as the growth of an extraordinary sensitivity: “O. would say little or nothing, but from time to time point to the cats, as though directing attention specially to them. Sometimes he might ask for something, or wish a dish set aside or a pie placed by his soup. But with such economy of words that ‘Go,’ ‘Take,’ and ‘Put’ seemed to cover almost all eventualities. If something were not required, the rest had learnt to remain still, both outwardly and innerly curbing any impulse to move, suggest or interfere—until the solution showed itself.”

Collin further describes how this atmosphere of sensitivity gave access to a more objective view: “For many hours at a stretch they became used to sitting in the Green Drawing Room with him, saying nothing, doing nothing. One’s eyes fell with pleasure on the bright spots of Persian and Indian miniatures against the restful green and gold walls, or on the chestnut tree beyond the window, on which day by day buds gave way to flowers and these to clusters of nuts. Nothing else was apparent. And yet in some way one’s whole attitude of life changed at such times, all impatience vanished and one became content to exist definitely in the present. This, it later became clear, was a very definite preparation.”

Rodney Collin’s growing understanding of how instinctive and mental habits hide insights and “quite new points of view” can also be found in an experience described in his unpublished manuscript: “O. seemed to find it difficult to sleep long and after two or three hours rest would wake again about 9:00 or 10:00 PM, take breakfast coffee, rise and begin another day. This would mean that Miss R. must serve lunch sometime after midnight, after which they might sit together for an hour or two and then go back to bed again. Next day O. might wake at 10:00 AM, there would be a second lunch at 2:00 PM, supper at 6.30 PM; then he would retire once more and so on. In this way, two complete days were compressed into 24 hours.”

One of these nights, after a midnight lunch, when “Miss Q. lay on the sofa and went to sleep and W. too was dozing,” Rodney Collin describes how he “for some reason remained alert and was filled with a strange awareness sitting there, the whole house asleep in this curious pause of the small hours, facing O. for hour after hour, the two of them quite silent and quite still. Awareness mounted and mounted in the silence and then suddenly gave out, drowsiness falling until hours later the dawn whitened the cracks in the shutters. It was strange, too, falling completely out of step with ordinary life; and curious when early or later ceased to have meaning because there was nothing to measure by. Was a meal a late lunch or an early supper and were they late retiring on Friday or early to bed on Saturday? All such ideas and, in fact, all ordinary ways of looking at the routine of life and passage of time were revealed as simply habits of thought. If a man was strong enough to create circumstances which break such habits, quite new points of view become possible.”

Collin found it more and more difficult to describe what was taking place because at this point he felt it necessary to admit the existence of miracles. They began to understand things which Ouspensky wished to convey to them without being told. In a single sentence and phrase they would see some extremely subtle and illuminating significance, which they knew very well they could have never invented for themselves. Moreover, they began to feel every gesture and situation as meaningful, as if they were in a play, where nothing is introduced which does not relate directly to the plot. Sometimes people and even common objects seemed to demonstrate the laws of three or seven. They gained the impression that Ouspensky was, in some inconceivable way, moving, arranging, combining and experimenting with human material without any visible or audible direction.

In such a situation there could be no countercheck. Each individual stood on their own experience of what happened, they could be believed or disbelieved, but nothing could be proved. If one were asked whether he had been told something by Ouspensky, he could not in the ordinary meaning say “yes,” and yet at the same time he knew very well that it was so. When those not present later asked, “What did O. say?,” it was impossible to answer because his broken phrases, if repeated verbatim, would have seemed nonsense to anyone not in the specially prepared state experienced by those who were present.

Indeed, the fact that nothing could be officially recorded, no pronouncement or plan attributed to Ouspensky, seemed an essential part of the intention. Everything had a tremendous range of meanings, which no one version could begin to exhaust.

~ • ~

Passing through the remarkable circumstances of this time, Rodney Collin gives several examples of what he found to be definite stages in a process of initiation conducted by Ouspensky, as when “personality was brought to the surface and accentuated to the highest degree, preparatory to being destroyed.” Collin observed himself beginning, “to act and pose with extraordinary arrogance, ‘Like a cross between an Indian rajah and the Grand Lama,’ as someone expressed it.” Another feature and capacity was his ability to record. When this feature was controlled by personality: “it gave rise to pride of authorship, intense belief in his exclusive way of interpreting scenes and events and thus to lying and the coloring of accounts to justify himself and bolster his own importance.”

Collin saw how he himself, and others, had three ways of meeting these temptations and opportunities. One either 1) fell into the temptation where personality took advantage of “what it liked,” or 2) recognized the temptation and tried to resist it more or less successfully, or 3) recognized that by accepting the temptation without reservation it became transmuted and brought an insight that was his “true course, the one for which he existed.” This third way he found possible only when personality was stripped as a result of one’s numerous experiences.

In late July, after assembling all he had understood in connection with the enneagram, Rodney Collin recognized that his own writing “was taking a line of its own,” very different from what he had planned. Extraordinary ideas and connections with their implications became accessible to him. He soon came to the conclusion that he himself could not lay claim to the ideas that entered his mind. He recognized them as broad abstracts, and that from his own mind and knowledge they took a form and developed. He did not have a theory regarding the source of these ideas and did not make any conclusions or attribute them to Ouspensky, although when he told Ouspensky of all of this he seemed to know very well.

Dr. Roles, who was one of Ouspensky’s old followers and undoubtedly one of his important assistants, was also regularly at Lyne at this time, but seemingly not taking part in what was revealed to the more intimate group. On October 1st when Roles found Ouspensky on the landing dressed and ready to meet the others, he protested: “I beg you not to go.” Ouspensky looked straight through him and pulled him down the stairs. After, when the group had gathered in the Green Drawing Room and had been sitting in silence for some time, Dr. Roles broke the silence saying: “Many want to know how to understand reconstruction.” Ouspensky did not answer. In the unpublished material, Collin states that some of them saw in this moment that the meaning of reconstruction would grow clear only when all that was happening was understood, and that this understanding would grow from the unity of those present. They continued to sit in silence for a very long time. Then Dr. Roles asked again: “How are we to make demands on ourselves?” in answer to which Ouspensky made some indefinable gesture. Collin says in his notes that he felt that Miss Q. had expressed their feeling when she eventually said: “Perhaps it would be better just to sit and understand, rather than ask questions.”

From Rodney Collin’s perspective, it was obvious that what took place at Lyne was understood very diversely by the different people there. I also think that this meeting illustrates some vital aspects of why later, after Ouspensky’s death, many of his followers were to gravitate toward either Dr. Roles or Rodney Collin.

~ • ~

The many car journeys undertaken by Ouspensky in the last months of his life have been wrongly attributed to Rodney Collin’s inventiveness. According to the unpublished material, these journeys (except for the trip made on Thursday, September 11th) were clearly made on Ouspensky’s own initiative. His decision to go for car journeys was already apparent in the evening of Thursday, September 4th after arriving at Lyne from Southampton, when he refused to leave the car: “Eventually he got out with Miss R., climbed up to the hall, took off his hat and coat and then very deliberately walked back to the car again and got in. ‘This is not the right Lyne,’ he said, ‘let’s go and find another.’” Nobody seemed to understand, and after some time he said in a very pleasant way to Rodney Collin: “Well what is the matter?” Collin replied: “I don’t seem to be able to think of anywhere better to go at the moment.” Ouspensky then said: “Let’s go anyway.” The chauffeur was roused up, and they went to Chertsey and came back after 20 minutes.

On Friday, September 12th they set out for a trip to Wendover. This time Collin sensed that there was “a greater air of purpose about the whole expedition” and that he “tried hard to become sensitive to any hints and suggestions which might be given.” That night after the trip Collin wrote: “There is some special problem to be solved here. We have not solved it yet. But this is the most extraordinary time: all kinds of barriers are crumbling and almost anything is possible.”

On Saturday, September 13th Collin was called to Ouspensky’s bedroom and Ouspensky asked if they could start very early the next morning. They left early Sunday morning for Dymchurch and after returning at 8:30 PM, 12 hours later, Collin observed that Ouspensky’s ‘unreasonable’ strivings turned his companions against him: “For this was a test of them and to bring them to a state where they could give up every impulse of self-will and accept all. Only when one observed, was it seen that every ‘unreasonableness’ and every test was at the cost of his own suffering.”

It was through these frequent car journeys that reconstruction, to him, came to mean reconstructing the whole of man’s life, all his experience, all that he has been told and learned and encountered. He also came to a deeper understanding of ‘will’ as a force by which man can do the impossible.

~ • ~

After Ouspensky’s death, the household at Lyne place grew anxious when Rodney Collin, locked up in Ouspensky’s adjoining dressing room, refused to respond to any attempts of contact. After several days suddenly the bell from Ouspensky’s room rang in the kitchen. Janet, Rodney’s wife, was the first to enter the room and found Rodney sitting cross-legged on Ouspensky’s bed. She found it very difficult to communicate with him and told Joyce later that he looked very strange and childlike. In Mexico, years later, he told Joyce that Ouspensky had invaded his being and that he received direct messages of extraordinary power and depth. The basic structure of the four interpenetrating levels of existence in his book, The Theory of Eternal Life, was perceived in this solitary period.

Within a short while after Ouspensky’s death, Janet and Rodney Collin decided to leave Lyne Place and moved to St. James’s Street in London, where he, without delay, shut himself up in his study and started the writing of The Theory of Eternal Life. The inner changes that had taken place subsequently to the experiences he had undergone were remarkable. An innocent, childlike and trustful temperament dominated his mind-set and his dealings with others. An increasing number of people were seeking him out, and his wife held the many callers at a distance so that he could work uninterrupted.

After this intense period of writing they decided to move to Mexico. Several people from Ouspensky’s former group wanted to join them. Dr. Roles who had taken command of the group found it apparently regrettable to see how people were drifting away. However, Joyce Collin-Smith told me on several occasions that Rodney was never seeking disciples. People were attracted by his being, his mild and gentle manners, and his knowledge. He was very clear about not imposing anything on others, and only explaining when people asked and really wanted to know for themselves, and he stressed the necessity to answer only from one’s own understanding and one’s own examples.

After settling at an old hacienda in Tlalpan, Mexico with those that had followed him from England, the group was soon outnumbered by people from the local community and the meetings were, before long, held in Spanish. Among the many activities Rodney Collin initiated, varying from mining, weaving of classical Aztec blankets, establishing the first English bookstore in Mexico City and arranging for his books to be published in Spanish, he started the building of a planetarium at Tetecala in the high hills 20 miles outside Mexico City. The planetarium was meant to be an architecturally symbolic construction with chambers for movements, lectures, theatre performances and a library for Work-related activities.

For a man to whom it has become obvious and clear that only the heart can reconcile inconsistencies, serving becomes a necessity. In his lectures, Collin focused the attention more and more toward the need of giving service to the people of the world and the needs of the planet. Recognizing the lack of health care in the local area, his wife Janet set up a clinic and employed a doctor. Never sparing himself physically, Rodney Collin was in much demand, answering questions from individuals and conducting groups. The focus was constant growth of being, and awakening of consciousness. As a result of the Work-literature being translated into Spanish by Sol Edicon, groups were started in Argentina, Peru, Chile and Uruguay. Ever vigorous, Collin helped and supported whenever and wherever he could. Regularly people flew in from America and Latin America to see him. Amongst them were Hugh Ripman and Robert de Roop. He also kept an extensive and profound correspondence with many people from all over the world. Joyce Collin-Smith told me that she thought he was not getting enough rest and that she had told him, but he had simply said: “One has to do what one can.”

In the midst of March 1956, Rodney Collin made every effort to settle all his business affairs; nothing should be unresolved. He told his wife: “All debts must be paid before moving on to something new. And I know that something new has to begin. The trouble is that I don’t know what it is. I can’t see clearly how to begin anything.” He added: “This journey to Peru is tremendously important. There, something very big is going to begin.” One month later on April 24th they left Mexico for Peru together, with John Grepe and Mrs. Dickens.

After a week in Lima, on May 2nd, the Collins went by plane to Cuzco. During the flight in an unpressurized plane that went up to 19,000 feet, Rodney Collin fell asleep and lost the mouthpiece that supplied oxygen. Janet, who was seated in front of him found out by accident and helped him, and the oxygen soon woke him up. This incident and the fact that Cuzco has an altitude of 11,500 feet might explain why in the next 24 hours, to his wife’s surprise, Collin took several doses of coramine drops (a stimulant used widely at that time to treat altitude sickness). With the exception of aspirin, he never took any medicine whatsoever.

After a short rest at the hotel, Rodney Collin went for a walk and said he would be back at 3:30 PM for a planned sightseeing tour. Janet went downstairs at 3:30 to meet Sr. Spinoza who was to take them to some ruins. He told her that Rodney was in a shop across the street dressing up a poor crippled boy he had come across. Afterwards she was told by a newsvendor who was so impressed by Rodney’s attitude toward the boy that he had followed them to see what would happen. The newsvendor told her that they went to the public baths where Rodney had washed the boy and dried him with his own shirt. As they came out of the shop, a crowd of people that had gathered outside followed them. At a certain moment Rodney turned and faced the crowd and said: “This boy is your responsibility. He is yourselves. You must pray to Our Lord to make him well. If you pray enough he will be healed. You must learn to give, to give. You must learn to look after each other. You must learn what is harmony.” A voice in the crowd said: “That’s all very well for you, you are rich.” Rodney Collin said: “Everyone can give something. Everyone can give a prayer. Even if you can’t give anything else you can always give a smile. That doesn’t cost you anything.”

Later the same day the Collins went by taxi to the Cathedral of Santo Domingo together with the boy (whose name was Modesto) and Sr. Spinoza. Outside the church a little girl was crying loudly. Rodney went up to her, but left her and gave her no more attention when he observed that she was crying out of temper. They then all went into the church where Rodney led them to the rail before a side altar where they knelt. He said: “In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Ghost we pray that this boy may be healed.”

The following night he woke up Janet and said: “I am afraid. I think I have done wrong. It seemed so important that the boy should be healed that I offered my own body in exchange for his. Now I realize that I was prepared for other work.” She told him: “If God has other work for you, do you think that some words you said will make Him change His plans?” He told her: “If you invoke the name of the Holy Trinity, as I did, what you ask will be done.”

In the morning Rodney went alone to communion. After breakfast John Grepe, Mrs. Dickens and the Collins were going to see some ruins outside town. As they were about to enter the car, Modesto came up saying he wanted to show Rodney where he lived in the belfry of the cathedral. They all drove to the cathedral, where Rodney Collin and Modesto went up the stairs to the belfry joined by John Grepe. Later, returning from the tour, they went back to the hotel. After lunch they went to their room to rest. Janet fell asleep, but became vaguely aware that Rodney had got up and gone out.

She woke suddenly hearing the clock in the cathedral strike. She looked at her watch, it was 3:15 PM. She went downstairs and out onto the steps of the hotel looking for her husband. Mrs. Dickins and John Grepe joined her as they were all going to visit some other Inca ruins. A man came up to them asking if they had been with the Señor Collin. He told them to go to the hospital as there had been an accident. When they came to the hospital they were shown into a small room. Rodney Collin was lying on his back on a stretcher on the floor. His broken right leg was drawn up in exactly the same form as the crippled boy’s.

Janet was later told by a man that as he was driving across the cathedral square, he had slowed down his car and looked up to verify his watch, and had seen Rodney Collin fall as the clock began to strike at 3:15. According to a woman who also saw him fall, he had fallen upright with his arms stretched out as a cross, with his head back as if looking up. Later the bell-ringer in the cathedral gave an account of what had happened. According to the boy, Modesto, Rodney had come to the belfry to tell Modesto that he was going to arrange for a doctor to operate and straighten his leg. As they were sitting and talking together, Rodney, leaning his back to the belfry arch, suddenly stood up with a gasp, hit his head on a beam, and then fell over the edge of the tower.

Rodney Collin was buried in an old church wall in Cuzco. On a flat stone is written the prayer he wrote one month before he died:

I was in the presence of God,

He sent me to earth,

I lost my wings,

My body entered matter,

My soul was fascinated,

Earth drew me down,

I reached the depth.

I am inert,

Longing arises,

I gather my strength,

Will is created,

I receive and meditate,

I adore the Trinity,

I am in the presence of God.

~ • ~

Publications by Rodney Collin-Smith

Palms and Patios: Andalusian Essays, London: Heath Cranton Limited, 1931.

The Theory of Eternal Life, London: Limited edition of 600 copies, 1950; Cape Town: Stourton Press, 1950.

Hellas: A Spectacle with Music and Dances in Four Acts, Cape Town: Stourton Press, 1951.

The Theory of Celestial Influence, London: Vincent Stuart, 1954.

The Theory of Conscious Harmony, London: Vincent Stuart, 1958.

The Mirror of Light, London: Stuart & Watkins, 1968.

| Copyright © 2015-2018 Terje Tonne This webpage Copyright © 2015-2018 Gurdjieff Electronic Publishing Revision: January 5, 2018 |

THE LEGACY OF RODNEY COLLIN

By Anthony Craig

(New Dawn – May/June 2000)

The following article examines the life and work of Rodney Collin, following on from Anthony Craig’s article about P.D. Ouspensky that appeared in the last issue of New Dawn.

The title of P.D. Ouspensky’s introduction to the esoteric system was “In Search of the Miraculous,” a title which he felt uncomfortable with, but nevertheless epitomised his life.

|

In his short life Collin achieved |

According to one of his pupils, Rodney Collin, Ouspensky finally achieved that level of being for which he had been working for his entire life. The events surrounding the death of this great Fourth Way teacher could certainly be called miraculous according to Collin’s testimony. Only days before, Ouspensky had despaired at the results of his repeated attempts to throw the responsibility for his follower’s inner work squarely on their own shoulders and had said that he was abandoning the system. After his death he apparently appeared to several people, and made some sort of intimate communication with Collin himself.

When Ouspensky died Collin locked himself in the room with his teacher’s body for several days despite repeated attempts by others to enter, and received many revelations that were to become the basis for his magnum opus The Theory of Celestial Influence.

He undoubtedly underwent some kind of regeneration for when he emerged he was a changed person, very childlike and innocent. Initially he was largely indifferent about attracting followers and concentrated on writing the book, but he was accused of hijacking students by Francis Roles who had salvaged the remainder of O’s followers and made Collin and any who followed him persona non grata.

Roles’ teaching had become diluted (in the opinion of his sister-in-law Joyce Collin-Smith); no longer was there the admonition to “believe nothing” and verify all for oneself, but to follow blindly. Collin, on the other hand had injected new life into the teaching without abandoning the fundamentals given to him by his teacher.

There is often a conflict between those who would like to keep the system “pure” and those who believe its existence depends on new forms and applications. Collin has been accused by many of the Ouspenskian “old guard” of taking the Fourth Way into places it wasn’t meant to go. Following his new beginning in a different country he took the teachings into a sphere where service to people and attention to the needs of the planet were essential. For Collin there was only one way to keep the system pure, and that was by coming pure oneself.

To remember oneself, to be free from egoism, to be kind, to be understanding, to serve the Work and one’s fellows, to remember oneself and find God...

Collin had been a journalist after leaving the London School of Economics and attended some lectures given by Nicol and eventually met Ouspensky in 1936, recognizing that here was everything he had been searching for. He and his wife lived with the Ouspensky’s both in Lyne Place and Franklin Farms in Mendham, NY when they moved to the US. He became deeply attached to Ouspensky and spent more and more time with him. While he had absorbed all the knowledge his teacher had given him, he now concentrated also on what his teacher was demonstrating himself.

In the time before and since his death, for myself and many others, the whole idea and purpose of the work revealed itself in quite a different way. It became clear that before, we had taken everything in an extraordinarily flat, incomplete way. By demonstrating a conscious dying, Ouspensky seemed to show that in this lay all possibilities.1

Collin was a mild and amiable man, modest and humble in the extreme, but with a quality of dignity and authority, and perhaps a little too trusting which allowed people to drain his resources and even swindle him. Joyce Collin-Smith said he put himself at everyone’s disposal, even rising from the meal table or from bed to attend anyone who asked to see him.

“The more demands that are made on me the better,” he answered. “I must do what I have to do.” “And what is that?” “Obey O.’s will.” Collin believed his mission had come from Ouspensky, to reconstruct the system and to find a new home for it. The new home was the only country, in Collin’s view, full of fresh possibilities — Mexico.

Rodney Collin

|

He wrote that Mexico had a “spring-time feeling,” of growth, expansion and development, a “new, unspoiled start.” In 1948 he, along with his wife Janet and a small party, arrived first in Guadalajara, and eventually settled in Tlalpan, where a nucleus of a permanent group was formed.

In his short life Collin achieved an incredible amount, in addition to a stunning unification of science and mysticism in two remarkable books. In Mexico he established Ediciones Sol publishing which translated Ouspensky’s, Maurice Nicol’s and other Fourth Way works into Spanish; he started the only English bookshop in Mexico City, the Libraria Brittanica; he had acquired a mine that could yield silver, salt and various nitrates; he bought an old hacienda and installed there a group of peasant women to weave blankets and serapes for tourists; his wife Janet opened a clinic and employed the services of a doctor from the city to attend there, and with a band of helpers made clothes for the poor; he formed a theatre group which staged productions of “Peer Gynt” and Anouilh’s “The Lark.”

His major project was the building of a planetarium hewn into the volcanic rock. It consisted of two interlinking circles below ground level, called the Chamber of the Sun and the Chamber of the Moon. Between the two was a small circular space where a large upturned shell on a pedestal caught the sun through an aperture above at the summer solstice. The two chambers were surrounded by a narrow, curving passageway, the walls adorned with mosaics showing the development of man, from the primordial forms of life to the perfect man. It also contained a lecture hall, to be used also for ritual or national dancing, exercises and the Gurdjieff-style ‘movements’ which were used to develop concentration and attention, and a library. He had enormous creative drive and boundless energy.

He was in so much demand to answer comments and questions and deal with matters of a philosophical nature, that it was difficult to get a word with him at all. To do so one must pick up tools or implements and work with or beside him on whatever was then demanding his attention.2

Collin felt that only through making increasing demands on himself could the Great Work be accomplished. This is what Ouspensky had taught him in the last few weeks of his life. But it was eventually to be his downfall. He had tried marathons of endurance, walking long distances in the heat, without water and rest, sometimes continuing for several days. He was becoming increasingly exhausted.

There entered into the Collin circles a Mexican woman named Mema Dickins, a devout Roman Catholic and a natural medium who had supposedly received visitations from Ouspensky to contact Collin. She passed on a variety of ‘messages’ to him, and he accepted her with his “childlike grace.” The circle was divided: some people disliked Mema on sight and distrusted her while others worshipped this oracle with increasing reverence. Collin believed that with her help it would be possible to find the traces of Fourth Way School through history.

In late 1955 Collin went to Paris, Seville, Athens, Rome, and Istanbul and felt he had found traces of ‘school’ in a number of areas, and wrote about Cosimo de Medici, about the house of Lorraine and Leonardo da Vinci, and various other well known historical figures whom he claimed had been ‘schoolmne’. While in Rome he was received into the Roman Catholic Church, a move that also brought criticism from some quarters but obviously added depth to the system for him. The work not a substitute for religion. “It is a key to religion, as it is a key to art, science and all other sides of human life.”

As a result of the distribution of the Ediciones Sol books several groups were started in Peru, Chile, the argentine and Uruguay which Collin kept in regular contact with. Collin had taught himself astrology and according to Joyce Collin-Smith knew that “something new is about to happen” to him. During Mass in the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and after an all-night pilgrimage on-foot, he apparently fainted from exhaustion, though later it was thought it was the first of a series of heart attacks which eventually killed him.

In the last few weeks of his life he drove himself especially hard and complained of feeling “rather strange” in the high altitude of Cuzco. He had discovered a crippled beggar-boy in the cathedral and had washed him in the public baths with his own shirt and promised him that Christ would heal him. The next day the boy took him to where he lived, in the belfry of the cathedral tower.

While talking he was looking at the statue of Christ on the mountain opposite, he stood up with a gasp as though his breath had failed, staggered forward onto the top of the low wall, grasping the two wooden beams that were supporting the arch. Then he fell forward, striking his head against one of them. His body fell onto the wide cornice that juts out below and slipped off, falling to the street below. He lay where he fell, his arms out sideways in the form of a cross, his eyes open as though looking up at the sky, smiling.3